After its delayed start on 1 June 2023, the Unified Patent Court (UPC) has now been in operation for six months.

We have delved into the statistics and early decisions of the UPC to see what we can learn from these first six months. While it is unwise to draw too many conclusions from a relatively small dataset, some clear messages are emerging, as we discuss below.

1. The UPC will be a busy court

In the months and years leading up to the start of the new system there was considerable curiosity about whether the UPC would see many cases, and who would be using it. The statistics for the first six months of operation give us some answers to those questions.

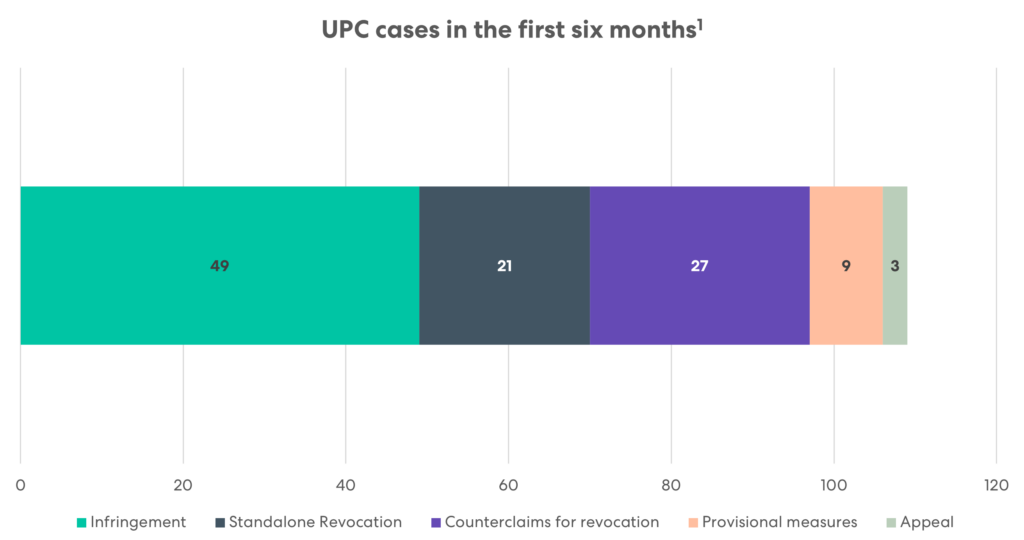

Over 100 cases[1] have been filed to date, in a range of different technologies, and by claimants of different sizes. So it looks like the UPC will be a very busy court.

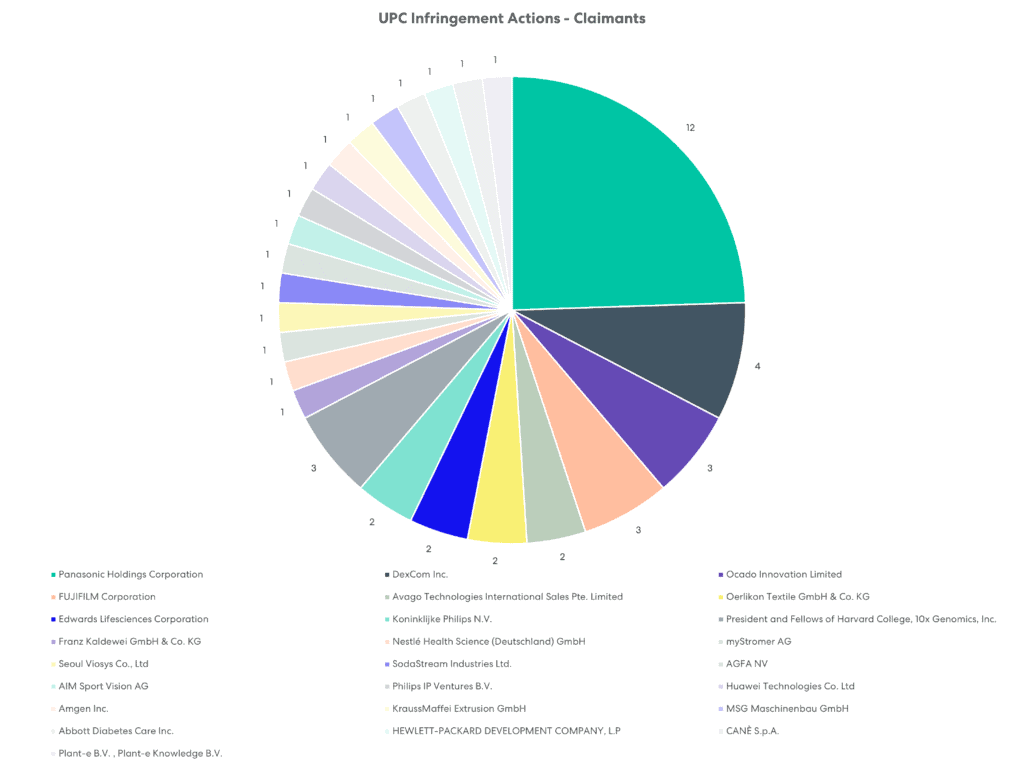

Some big names appear on the list of claimants in the infringement cases that have been filed so far. Panasonic has filed almost a quarter of the infringement actions so far, using the UPC as another front in its global standards essential patent battle with Oppo and Xiaomi. Similarly, Ocado has filed three infringement cases against its long-time rival Autostore.

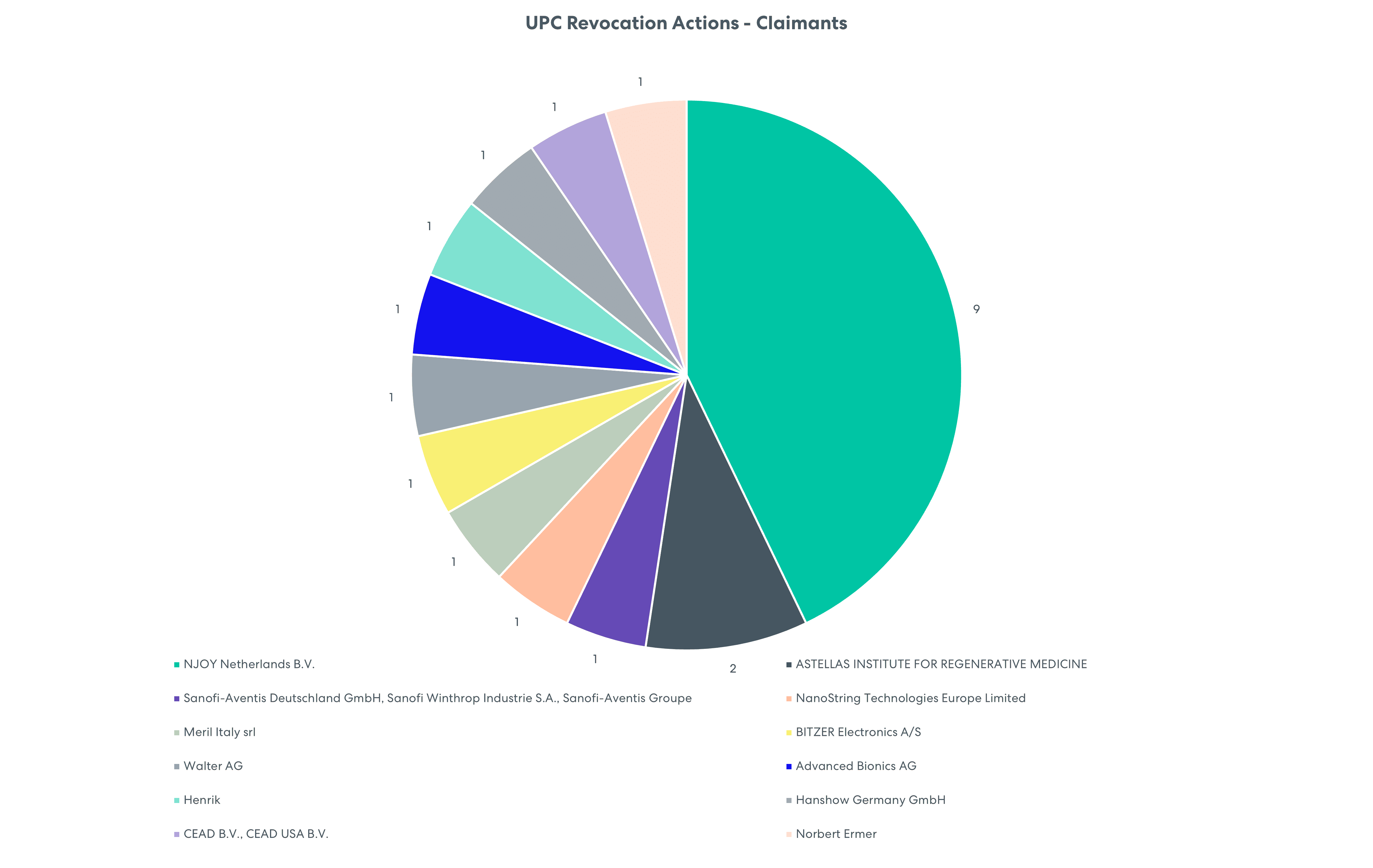

The presence of such big hitters among the early adopters of the UPC will be seen as a vote of confidence in the new court, but it will be gratifying to many to see smaller companies like the 140-employee ebike maker myStromer getting involved, as this shows that progress is being made towards the aim of facilitating patent enforcement and defence for SMEs. Indeed, the list of claimants in the first central revocation actions is dominated by smaller companies looking to the UPC as a cost effective option for clearing their path to market by sweeping competitor patents out of the way.

2. Getting opt outs right is crucial

Of course, not everyone has been enthusiastic about the UPC, and many patentees have exercised their right to opt their patents out of the UPC’s jurisdiction. According to the UPC’s Case Management System, almost 420,000 opt outs were filed during the three-month sunrise period immediately preceding the 1 June 2023 opening date of the UPC, and opt out numbers have continued to increase in the months since, as patentees opt out newly granted or published applications and cases that were missed during the sunrise period.

Getting your opt outs right is of critical importance, as we’ve seen in a couple of early decisions from the UPC.

In the case of AIM Sport Vision vs. Supponor[2], the Helsinki Local Division held that AIM Sport’s withdrawal of the opt out of its European patent no. EP3295663 was ineffective, because it was performed after infringement and invalidity proceedings were initiated at the German national courts, even though those proceedings were brought before the UPC came into effect.

The result is that AIM Sport Vision is now locked out of the UPC for this patent – if it wants to sue for infringement of this patent it will have to do so in the national courts, at considerably greater expense than a single action in the UPC.

In Cup&Cino and Alpina Coffee Systems[3], the Vienna Local Division confirmed that an (apparently unauthorised) opt out filed for Cup&Cino’s European patent no. EP3295663 after an application for a preliminary injunction had been filed at the UPC was invalid, meaning that Cup&Cino is locked in to the UPC for that patent. In this case that is perhaps not a problem to Cup&Cino, since it was already seeking to enforce its patent in the UPC, but it does highlight the importance of opting out before any action is brought in the UPC if you don’t want your patent to be subject to the UPC’s jurisdiction.

3. Preliminary injunctions are available

There was also a lot of speculation before the UPC opened its doors as to how it would approach preliminary injunctions. Would it be very pro-patentee and issue preliminary injunctions easily, or more conservative?

Judging by the first few preliminary injunction decisions, the answer is that the Court is adopting a balanced approach, and is rigorously applying the tests set out in the UPC Agreement and Rules of Procedure.

What that means is that the UPC will grant preliminary injunctions, but patentees seeking preliminary injunctions will need to:

- be thorough in their applications, making the case not just for infringement but also validity of the patent being enforced;

- file the application for a preliminary injunction as soon as possible; and

- make a convincing case on the balance of convenience, to convince the judges that the patentee will suffer more from not getting an injunction than the defendant will if an injunction is granted.

The UPC has shown in the early cases that it’s not afraid to go into a lot of detail on the question of infringement. If it has any doubt as to whether there is infringement, or whether the patent is valid, it won’t grant an injunction.

Businesses should welcome this rigorous approach, as it shows that the UPC is conscious that ordering a business to stop trading in a product is not a step to be taken lightly.

For example, in the very first preliminary infringement case[4], the applicants 10X Genomics and the President and Fellows of Harvard College sought a preliminary injunction restraining infringement of European patent no. EP4108782 (“Compositions and methods for analyte detection”). In a written decision running to over 100 pages following a hearing lasting a day and a half, the Munich Local Division granted the requested injunction, having found:

- a high likelihood that the patent was valid (despite a pending Opposition filed by one of the respondents);

- a high likelihood of both direct and indirect infringement by the respondents ;

- there had been no unreasonable delay in requesting the preliminary injunction;

- the damage threatened by the alleged infringing product was sufficient to warrant a preliminary injunction; and

- the interest of the applicant in not having its rights infringed outweighs the interest of the alleged infringer in securing market share in a developing market.

In contrast, in a second decision involving the same parties in which the applicants sought a preliminary injunction restraining infringement of EP2794928 (the parent of EP4108782) the Munich Local Division refused to grant a preliminary injunction, because:

- it was not convinced that there was infringement of the patent as granted;

- it was not convinced of the validity of the patent; and

- there had been an unnecessary delay in requesting a preliminary injunction, as proceedings could have been brought in national courts earlier, as the patent was granted on 20 February 2019.

Similarly, in Cup&Cino and Alpina Coffee Systems, the applicants sought a preliminary injunction restraining infringement of EP3398487 (“Method and device for producing milk foam”). The Vienna Local Division was not convinced, following a detailed inspection of the allegedly infringing product, that there was any infringement of the patent, and so the application for a preliminary injunction was refused.

In contrast, in myStromer vs. Revolut Zycling[5], the applicant sought a preliminary injunction restraining infringement of EP2546134 (“Combination structure of bicycle frame and motor hub”). The Dusseldorf Local Division agreed that the application was sufficiently urgent to warrant an ex partes hearing, because an allegedly infringing product was being exhibited by the defendant at an ongoing trade fair.

The Dusseldorf Local Division granted the preliminary injunction, having been satisfied that:

- the patent was infringed;

- there was sufficient evidence of validity, as the patent was granted in 2015 and there had been no subsequent EPO Opposition or national invalidity proceedings;

- there was sufficient evidence of irreparable damage to applicant if an injunction was not granted.

4. Orders for preservation of evidence

Some of the other preliminary measures that the UPC can order may be unfamiliar to users of other court systems, so remedies such as orders for preservation of evidence attracted a lot of interest in the run up to the launch of the UPC.

Some early decisions provide an indication of how the Court will approach these measures. The Court has shown a willingness to hear applications ex partes in cases of extreme urgency, and to grant orders for preservation of evidence where the applicant has met the threshold for evidence of likely infringement and validity of the patent and has indicated an intention to bring an action for infringement.

But the Court is again adopting a balanced approach, attaching conditions such as allowing only named individuals to gather evidence and restricting the use of the evidence gathered only to substantive proceedings relating to the same case. Potential defendants can therefore have some confidence that their competitors won’t to be allowed to use an order for preservation of evidence as an excuse to take and use their competitors’ sensitive information.

In Oerlikon Textile vs. Bhagat Group[6], the Milan Local Division heard an application for an order for preservation of evidence in respect of an alleged infringement of EP2145848 (“False twist texturing machine”). The application was heard on an ex partes basis, due to the imminent end of an international trade fair which gave rise to a risk that relevant evidence would be lost.

The Milan Local Division granted the order for preservation of evidence, because:

- the applicant declared an intention to bring an action for infringement;

- the applicant established ownership of the patent;

- there was a high likelihood that the patent was valid, as there had been no post-grant Opposition; and

- there was documentary evidence supporting allegation of infringement.

A similar order was granted in Oerlikon Textile vs. Himson Engineering[7]

5. Orders for inspection of premises

Orders for inspection are another remedy that can be sought from the UPC. The UPC has the power to allow a claimant to enter a defendant’s premises to gather evidence, and has shown that it is willing to use that power.

However, the bar for granting an order for inspection is high. The applicant must make a good showing of validity and infringement of the patent, and explain what evidence is needed and why.

And even if the Court does grant an order for inspection, again there will be conditions attached to prevent misuse of any evidence gathered.

In Progress Maschinen & Automation vs. AWM S.R.L. and Schnell[8], the applicant requested an order to inspect premises and preserve evidence in respect of an alleged infringement of EP2726230 (“Method and device for continuously producing a mesh-type support”). The Milan Local Division heard the application on an ex partes basis, because there was a risk that the defendant would destroy evidence if it was made aware of the action.

The Milan Local Division granted the order, because:

- the applicant indicated an intention to bring an action for infringement, relying on the evidence obtained by the requested inspection;

- the applicant established its ownership of the patent;

- there was sufficient proof that the patent was valid, as a post-grant Opposition had been filed but rejected by the EPO with the patent being maintained as granted; and

- there was sufficient evidence supporting the allegation of infringement.

6. The UPC has teeth

One other thing that has become clear from the early decisions of the UPC is that this is a Court that has teeth and is not afraid to use them.

In myStromer vs. Revolut Zycling, the Dusseldorf Local Decision issued a preliminary injunction prohibiting Revolut from selling or offering infringing e-bikes in a number of countries.

The order was served on Revolut at the Eurobike trade fair on 23 June 2023, but Revolut delayed taking its stand down until 6pm that day, and an Instagram post offering test rides was not taken down until the following day. More seriously, a test bike was supplied to a German retailer and was used during an open day on 24 September 2023.

The Dusseldorf Local Division found that the preliminary injunction had been breached by these actions, and ordered Revolut to pay a penalty payment of EUR26,500, as a deterrent against further breaches in future. The Division provided a rationale for the amount of the penalty, breaking it down as follows:

- EUR1000 for the continued operation of the stand;

- EUR500 for late removal of the Instagram post; and

- EUR25,000 for supplying the test bike.

Revolut was also ordered to pay 75% of the costs of the enforcement action.

This order sends a clear message that the UPC will punish financially those who ignore its orders.

The future of the UPC

The UPC has got off to a flying start, and it looks like the volume of cases it has to handle will only increase over time as its popularity increases further.

It will be fascinating to see the first final decisions and orders, which are expected to issue in the second half of 2024.

We are closely monitoring developments at the UPC and will bring you further updates. For more information on the UPC please visit the dedicated area of our website at or talk to one of our experts.

[1] Cases publicly accessible on the UPC Case Management System on 27 November 2023

[2] AIM Sport Vision AG vs. Supponor Oy; Supponor Limited; Supponor SASU; Supponor España SL; Supponor Italia SRL, UPC_CFI_214/2023

[3] Cup&Cino Kaffeesystem-Vertrieb GmbH & Co. KG vs. Alpina Coffee Systems GmbH, UPC_CFI_182/2023

[4] 10X Genomics, Inc. and the President and Fellows of Harvard College vs. NanoString Technologies Inc., Nanostring Technologies Germany GmbH and Nanostring Technologies Netherlands BV, UPC_CFI_2/2023

[5]myStromer AG vs. Revolut Zycling AG, UPC_CFI_177/2023

[6] Oerlikon Textile G.M.B.H. & Co. K.G. vs. Bhagat Group, UPC_CFI_141/2023

[7] Oerlikon Textile G.M.B.H. vs. Himson Engineering Private Limited, UPC_CFI_127/2023

[8] Progress Maschinen & Automation AG vs. AWM S.R.L. and Schnell S.P.A., UPC_CFI_286/2023

This is for general information only and does not constitute legal advice. Should you require advice on this or any other topic then please contact hlk@hlk-ip.com or your usual HLK advisor.