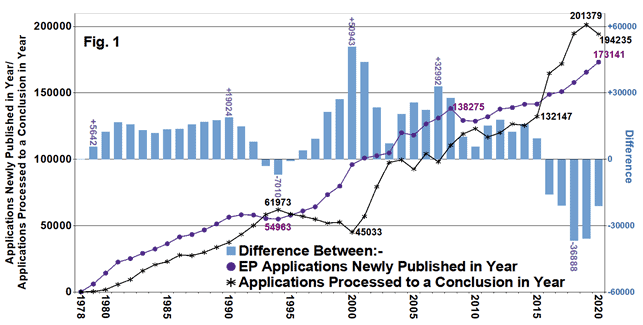

The number of European patent applications newly published in each year has increased greatly, if not always continuously, since the European Patent Office opened in 1978. The number of applications processed to a conclusion in each year (i.e. applications granted as patents, applications refused, withdrawn or deemed withdrawn) has also increased greatly, though again not entirely continuously. Generally, the number of applications newly published in a year has exceeded the number of applications processed to a conclusion in that year, with exceptions around 1994 and, much more markedly, since 2016. This is summarised in Fig. 1.

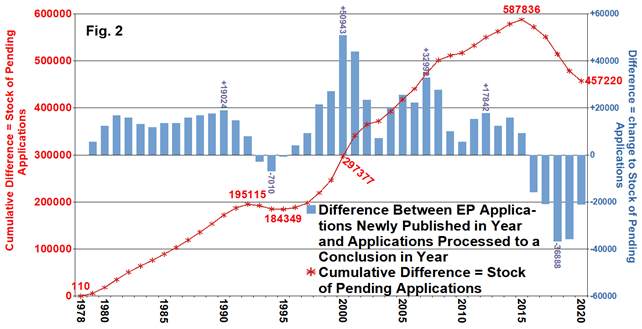

The numbers of European patent applications newly published year by year provide an indication of additions to the “stock” of European patent applications pending at the EPO. That stock of pending applications is then reduced year by year when applications are processed to a conclusion, i.e. when patents are granted and when applications are refused, withdrawn or deemed withdrawn. The difference between the number of applications newly published in a year and the number of applications processed to a conclusion in the same year represents the net change in that year to the stock of pending applications. Over the years the cumulative difference then represents the stock of pending applications. This is illustrated in Fig. 2.

As shown, the stock of pending applications generally grew until 2015, reaching a peak of 587,836 pending applications at the end of that year. Since then the stock has fallen – an increase in numbers of patents granted in recent years has been the primary driver of an increase in the total numbers of applications processed to a conclusion year by year, which since 2016 have exceeded the numbers of European patent applications newly published year by year. At the end of 2020 the stock of pending applications stood at 457,220.

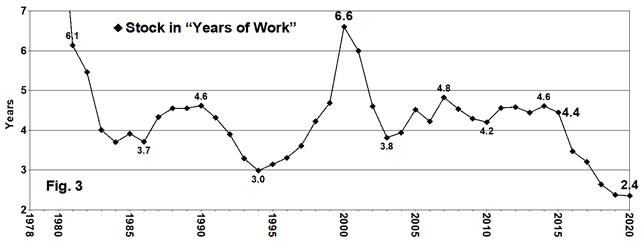

That stock of pending applications might still seem large but perhaps a useful way of viewing the stock is in terms of the number of years of work it might be expected to represent for the EPO. Of course, this depends on how quickly the EPO can process applications. In 2000, for example, 45,033 applications were processed to a conclusion (granted, refused, withdrawn or deemed withdrawn) and at the end of 2000 the stock of pending applications stood at 297,377. If the work of processing applications to a conclusion had continued at the same rate that stock of pending applications would then have been equivalent to over six years of work for the EPO. In 2020 four times as many applications – 194,235 – were processed to a conclusion and at the end of 2020 the stock of pending applications stood at 457,220. If processing of applications to a conclusion continued at the same rate that stock would now be equivalent to just over two years of work for the EPO. Fig. 3 shows how the stock of pending applications, in terms of “years of work”, has varied.

In various reports over recent years the EPO has published information – not always consistent information – about levels of stock. The most recently published information, in the “Quality Report 2020”, indicates that the stock at the end of 2020 was 11.7 months of available work (down from around 17 months at the end of 2015). Clearly the EPO estimates stock on a basis different to the simple “years of work” basis used above. The 2020 report indicates that the long term goal of the EPO is a stock of 11 months of available work.

The stock in terms of “years of work” might be seen as an indicator of an average time lag between publication and conclusion of processing of an application or as a “backlog” of applications. A decline in stock might be considered a welcome reduction of the time lag or “backlog”. On the other hand, some level of “stock” may be needed to ensure that resources needed to effectively process applications can be properly maintained and optimally employed.

Part 2 of “The European Patent Office – The Story in Numbers” looks in more detail at European patent applications processed to a conclusion in each year (i.e. applications granted as patents, and applications refused, withdrawn or deemed withdrawn). Has it become easier to get a European patent?

This is for general information only and does not constitute legal advice. Should you require advice on this or any other topic then please contact hlk@hlk-ip.com or your usual Haseltine Lake Kempner advisor.