The European Patent Office has developed a consistent approach to the examination of patent applications relating to alloys, taking into consideration the unique nature of these important industrial materials.

Our first article on patenting alloys at the EPO focused on clarity. In this article, we consider the EPO’s practice as regards novelty.

Novelty

The EPO’s approach to the assessment of novelty is strict: all of the features of a claim must be directly and unambiguously disclosed in the prior art for the claim to lack novelty. The meaning of directly and unambiguously disclosed, however, can depend to some extent on the technical context of the documents in question. When assessing the novelty of alloy claims, there are some particular considerations to bear in mind.

Compositional overlap

An alloy claim will typically define a chemical composition in terms of the amounts of each element present in the alloy, as in the following simplified example.

- Alloy comprising from 5 wt. % to 10 wt. % A and from 3 wt. % to 7 wt. % B, the balance being C and the usual impurities.

For a prior art document to destroy the novelty of this claim, it must disclose an alloy having a composition falling within these ranges.

Prior art documents, particularly patent documents, will typically disclose alloy compositions in two different ways:

- precise compositions of specific example alloys provided as evidence that the claimed invention can be put into practice and achieves the desired technical effect; and

- general ranges defined by lower and upper endpoints given for each element.

Specific examples

The assessment of novelty is relatively straightforward when considering only disclosures of the specific examples. If one of the examples has a composition falling entirely within the claimed ranges, the claim lacks novelty. For example, claim 1 above would lack novelty over a prior art example alloy consisting of 7 wt. % A and 3.5 wt. % B, the balance being C.

However, claim 1 would not lack novelty if the composition of the prior art example were to differ in terms of the amount of any of A, B or C, or if the composition were to include any further elements beyond impurity levels (because claimed alloy compositions are considered to be closed, as discussed in our article on clarity).

For example, claim 1 would be novel over an example alloy consisting of 7 wt. A and 2 wt. % B, the balance being C. It would also be novel over an example alloy consisting of 7 wt. A, 3.5 wt. % B and 1 wt. % D, the balance being C.

Ranges

The situation, however, becomes more complicated when the prior art disclosure is defined in terms of ranges for each element present.

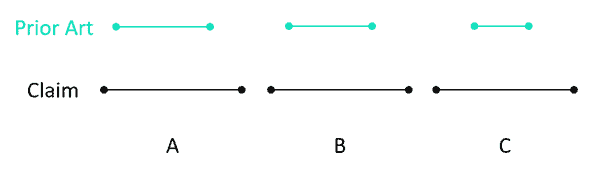

If each of the ranges disclosed in the prior art falls within the corresponding claimed ranges, the claim lacks novelty. This is illustrated figuratively below.

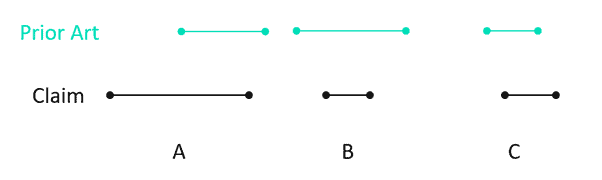

However, what happens if one or more of the prior art ranges are broader than, or only partially overlap with, the corresponding claimed ranges, as shown below?

In such cases, the EPO applies the rules relating to selection inventions set out in the Guidelines for Examination (Part G, VI-8). According to these rules, a sub-range selected from a broader range in the prior art is considered to be novel if:

- the selected sub-range is narrow compared to the known range; and

- the selected sub-range is sufficiently far removed from any specific examples in the prior art and from the end-points of the known range.

Of course, where one range partially overlaps another, the claimed range cannot be considered to be far removed from the end-points of the known range – by definition, one of the end-points of the known range will fall within the overlapping claimed range. Therefore, if there is only partial overlap in the ranges of one of the elements in the composition, and there are no other differences between the claimed alloy and the prior art disclosure, an EPO examiner can object that the disclosed end-point in the prior art is an explicitly disclosed value falling within the claimed range and therefore takes away the novelty of the claim.

However, the case law also requires examiners to take into account whether the skilled person would seriously contemplate applying the technical teaching of the prior art in any area of overlap. In Board of Appeal decision T 0261/15, for example, which concerned a patent for a pearlitic steel rail defined by a composition which overlapped with the prior art in terms of multiple components, it was decided that the limit values of a known range, although explicitly disclosed, should not be treated in the same way as the examples when assessing novelty. While the examples are disclosures of compositions which the skilled person would seriously contemplate implementing, the skilled person would not necessarily “seriously contemplate” working in the region of the end-points of general ranges.

In the particular context of alloys, the skilled person also knows that different alloying elements can interact with one another in an unpredictable way to produce precipitates and solid solutions, and so the skilled person does not make arbitrary compositional changes. Therefore, following T 0261/15, concentration ranges disclosed in the prior art should not be considered in isolation but must instead be viewed in combination. In addition, where there is overlap in terms of the amounts of more than one element in an alloy, the total conceptual area of overlap between the claims and the prior art is likely to be narrow.

Another relevant Board of Appeal decision (T 1571/15) concerned a patent for a nickel-based superalloy defined in terms of a chemical composition which overlapped with the broadest ranges of multiple components in a prior art document. Indeed, the patent claim even covered the centre of the broadest range for titanium disclosed in the prior art. However, the prior art also disclosed preferred compositional ranges which did not overlap with the claim, as well as an exemplary composition which fell entirely within the preferred ranges. The Board therefore considered there to be a pointer in the prior art to work within the preferred ranges and not to work within the broader ranges overlapping with the claim under consideration, such that the skilled person would not seriously contemplate working in the area of overlap (despite the claim covering the centre of the broadest range).

Accordingly, as long as none of the specific examples in the prior art fall within the area of overlap, it is often possible to overcome novelty objections based on overlapping ranges.

Implicit disclosure

In addition to the elemental composition, claims to an alloy often recite microstructural features or define physical or chemical properties of the alloy in terms of parameters. Such microstructural or parametric features may not be disclosed explicitly in the prior art or may not be directly comparable with the prior art disclosure. For example, a claim may define a microstructure in terms of a particular size of precipitate which is simply not mentioned in the prior art. Alternatively, a claim could recite the impact resistance of an alloy component as measured by Charpy impact testing at a particular temperature, whereas the prior art may disclose an Izod impact strength test at a different temperature. In such situations, it can be difficult to assess whether the claimed alloy is anticipated by the prior art, particularly where the elemental composition of the alloy is not itself new.

In such cases, an EPO examiner will often object that the claim to the alloy lacks novelty on the basis that the claimed feature or parameter would inevitably result in the prior art from application of the same manufacturing method to an alloy having the same chemical composition. That is to say, the prior art will be taken to disclose the claimed alloy implicitly or inherently.

When faced with such an objection, it can be tempting to amend the alloy claim to add further compositional or microstructural limitations which provide a clearer distinction over the prior art. However, in some cases, it is possible to overcome this type of objection by explaining why the manufacturing method of the claimed invention is different from that disclosed in the prior art. For example, if it can be shown that the claimed precipitate or impact resistance is only achieved when the alloy is heated under certain annealing conditions, and the annealing conditions disclosed in the prior art are different, then it is arguable that the precipitates or impact resistance are not implicitly disclosed in the prior art document.

When drafting alloy applications, we therefore recommend including explanations of the purpose of any manufacturing steps and the particular conditions used, and tying these back to the alloy microstructure and the desired properties. Comparative examples which evidence the effect of varying manufacturing conditions are also particularly helpful.

Further advice

Michael Ford is a Senior Associate in our Materials Group with extensive experience of protecting alloy inventions in Europe. If you would like further advice on this topic, please get in touch.