Stay connected with HLK

Keep up-to-date with the latest IP insights and updates as well as upcoming webinars and seminars via HLK’s LinkedIn page, or simply subscribe to our updates.

In this recent case before the High Court, Mr Justice Richard Smith dismissed the Claimant’s claim for trade mark infringement and passing off arising from the sale of continuous glucose monitoring systems by the Defendant. The Court found that the Claimant’s three-dimensional trade mark representing the “on-body unit” of a continuous glucose monitoring system was invalid and, as a result, it was not infringed. The judgment is noteworthy as it highlights the challenges of enforcing rights in shape marks by brand owners.

We explore the judgement further in our article below.

Paulina Kasprzak | Connect on LinkedIn | pkasprzak@hlk-ip.com

The Claimant, Abbott Diabetes Care Inc. (“Abbott”), is a market leader in the development, manufacture and sale of continuous glucose monitoring (“CGM”) systems, which are used by diabetes patients, athletes and wellness consumers alike. Abbott’s CGM products serve over six million users across 60 countries, with its first system, the Freestyle Navigator 1, launched as early as 2007.

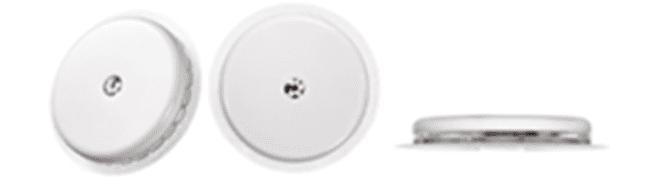

The Claimant successfully registered a three-dimensional trade mark at the UK Intellectual Property Office on 30 December 2022 under number 3779922 for “Sensor-based glucose monitors; continuous glucose monitoring systems” in class 10, as shown below (the “Mark”).

Abbott Diabetes Care Inc v Sinocare Inc & Ors [2025] EWHC 206 (Ch) (07 February 2025)

The Mark protects the “on-body unit” (“OBU”) which houses the sensor component and transmission electronics used in the Claimant’s CGM systems. While Abbott currently sells various CGM systems, the majority of its OBUs are identical in appearance.

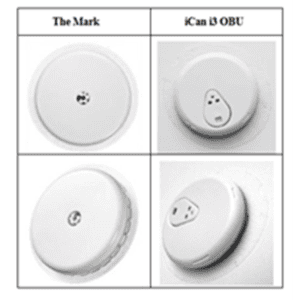

The three Defendants (together, “Sinocare” or the “Defendant”) manufacture and sell rapid diagnostic test products, including CGM systems, for chronic diseases. In 2023, Sinocare introduced its own CGM system, including the disputed iCan i3 OBU (shown below), to the Chinese market where Abbott also operates and has sold over one million products to date. Further, in January 2024, Sinocare began selling its systems in the UK through websites. Although its UK sales are currently low, Abbott claimed that Sinocare intended to significantly expand its presence in the EU and UK by targeting all the CGM market channels mentioned above.

Abbott Diabetes Care Inc v Sinocare Inc & Ors [2025] EWHC 206 (Ch) (07 February 2025)

Allegations

The Claimant argued that, due to the close physical relationship between the OBU and its user, the Mark was particularly unusual and valuable, being worn by users continuously and often visibly to others. It also maintained that the Mark acquired distinctive character through the substantive use that has been made of it over the years. The Claimant relied on survey evidence which, it argued, confirmed that the extensive use of the Mark had caused it to become a badge of origin in its own right.

It further claimed that the Defendant designed its own CGM system with the intention to saturate the European health care market, choosing an OBU design which not only closely resembled the Mark but was also significantly more similar to it than any other manufacturer’s design. The Claimant argued that the Defendant infringed the Mark on two grounds:

Abbott also contended that Sinocare could not rely on the defence under section 11(2)(b) of the TMA, which concerns the use of non-distinctive signs in accordance with honest commercial practices. Additionally, Abbott advanced a claim in passing off.

Defences

The Defendant, in turn, counterclaimed against Abbott, seeking a declaration of invalidity of the Mark, arguing that it was devoid of distinctive character (section 3(1)(b) TMA) and consisted exclusively of the shape or another characteristic necessary to obtain a technical result (section 3(2)(b) TMA).

The Defendant criticised the survey evidence relied on by the Claimant contending that it was not capable of testing the question of whether the shape of the OBU identified its trade origin as Abbott’s; the Defendant claimed that it provided no way of distinguishing those respondents who simply recognised the OBU as an Abbott product and those who not only recognised it as such but also appreciated that the shape was one that belonged exclusively to Abbott.

Validity of the Mark

The judge concluded that the Mark did not possess distinctive character for any category of relevant consumers, including health care professions (“HCP”), patients (or their carers) and wellness consumers. He held that, while the evidence relied on by the Claimant showed that these consumers were able to recognise the Mark and associate it with the Claimant’s products, it failed to demonstrate that they perceived the product’s shape alone as a badge of origin.

The judge also noted that Abbott presented the Mark in its marketing materials primarily as a product, emphasising its functionality and small size rather than its circular shape. He observed that Abbott’s traditional word and device marks carried the burden of badge of origin, and that Abbott had failed to educate relevant consumers on the secondary meaning of the Mark. This finding alone rendered the Mark invalid for lack of distinctiveness.

Mr Justice Richard Smith nevertheless considered the other ground of invalidity put forward by the Defendant. He held that the Mark consisted exclusively of the shape of goods which was necessary to obtain the sensor’s technical result. Therefore, section 3(2)(b) was also successfully argued in this case and the Mark was invalid for that reason too.

Trade mark infringement claims

Despite these findings, the judge nevertheless considered the Claimant’s trade mark infringement claims. Had the Mark been valid, the claim under section 10(2)(b) of the TMA would have failed due to the absence of a likelihood of confusion among relevant consumers. This was because:

Further, Abbott would not have succeeded in its section 10(3) TMA claim. Even assuming that relevant consumers would link the Mark with Sinocare’s similar OBU, Abbott failed to demonstrate that Sinocare’s use of a white, circular OBU would change the economic behaviour of those consumers, or that there was a serious likelihood of such a change occurring in the future. Therefore, neither of the two claimed harms – detriment to the Mark’s alleged distinctive character and an unfair advantage gained through association with the Mark – was made out. The judge also found that Sinocare’s use of its circular OBU was not without due cause and should be regarded as fair competition rather than something to be prevented.

Regarding the survey evidence relied on by the Claimant, the judge agreed that further questions, such as, the question of whether the respondents believed the shape of the OBU to belong exclusively to Abbott, would have been appropriate. He considered that instead the focus of the responses was on the product, what it did and how it worked, which was consistent with how the OBU featured in the Claimant’s marketing materials. His conclusion was that, given how the survey was framed and the familiarity of type 1 diabetics with diabetic devices it was unsurprising that many respondents recognised the Mark, however, this did not mean that they understood any white, circular OBU to come from a particular manufacturer.

Section 11(2)(b) TMA defence

Mr Justice Richard Smith also held that, considering all the circumstances, Sinocare acted fairly in relation to Abbott’s legitimate interests as the proprietor of the Mark and that the honest dealing defence would have been available to it for both infringement claims. This was particularly because Sinocare’s sign was non-distinctive and Sinocare demonstrated that it was unaware of the Mark’s existence when designing its OBU. Additionally, the circular shape was chosen for Sinocare’s product purely for functional reasons, specifically to minimise snagging, catching and detachment.

Passing off

Regarding the passing off claim, while the parties agreed that Abbott had goodwill in the UK, the key question was whether consumers identified that goodwill with the circular shape of the OBU. Since the Mark lacked inherent or acquired distinctiveness, the judge found that they did not. Further, as consumers did not treat Sinocare’s OBU design as indicative of trade origin, there could be no misrepresentation either. Therefore, Abbott’s passing off claim also failed.

What are the key practical points arising from this judgment?

Lastly, the decision echoes the Courts’ cautious approach toward enforcing rights in product designs based solely on their technical functionality. By ensuring that such designs are not monopolised through trade mark protection, they foster innovation and fair competition within the industry.

This is for general information only and does not constitute legal advice. Should you require advice on this or any other topic then please contact hlk@hlk-ip.com or your usual HLK adviser.

Keep up-to-date with the latest IP insights and updates as well as upcoming webinars and seminars via HLK’s LinkedIn page, or simply subscribe to our updates.