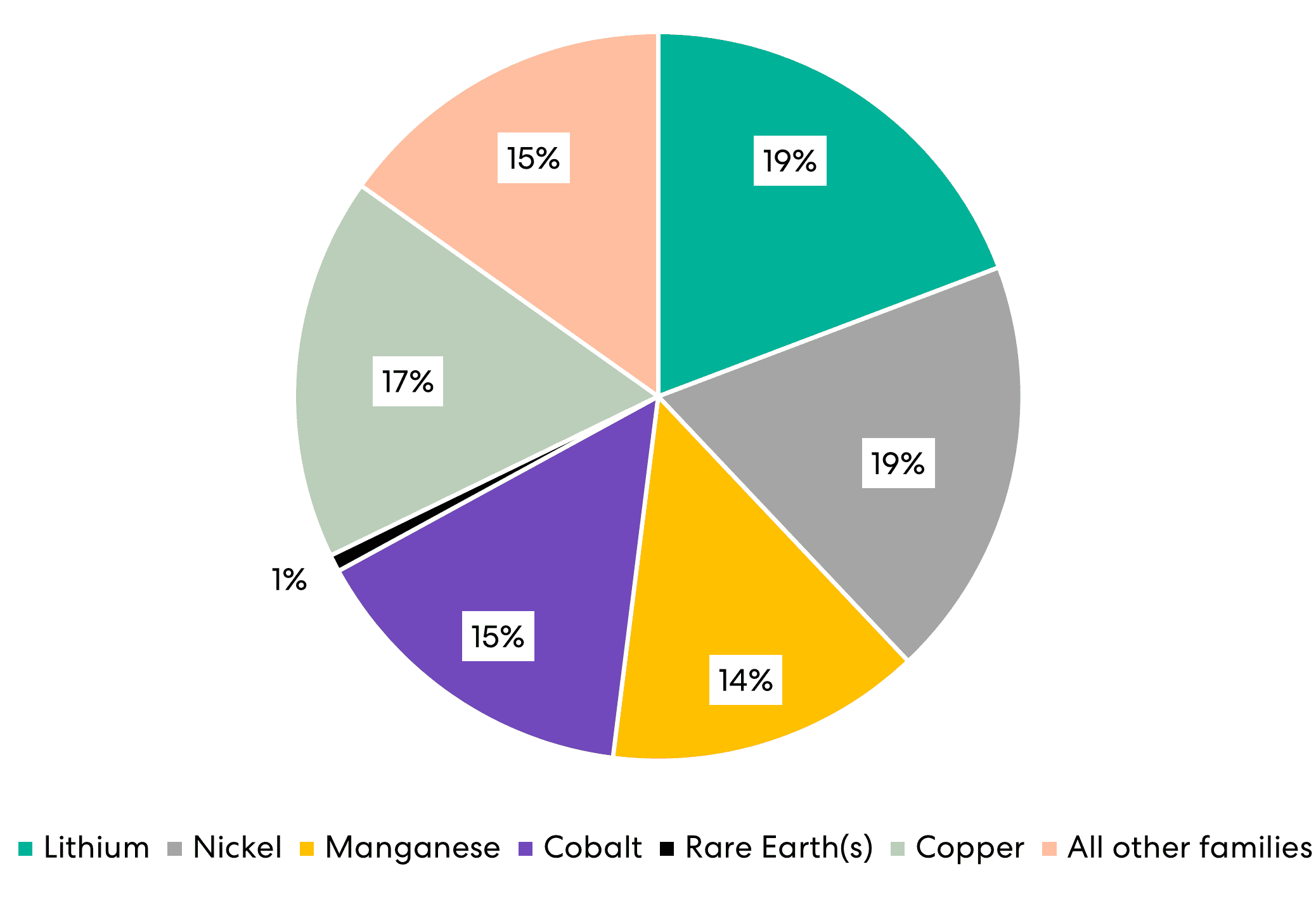

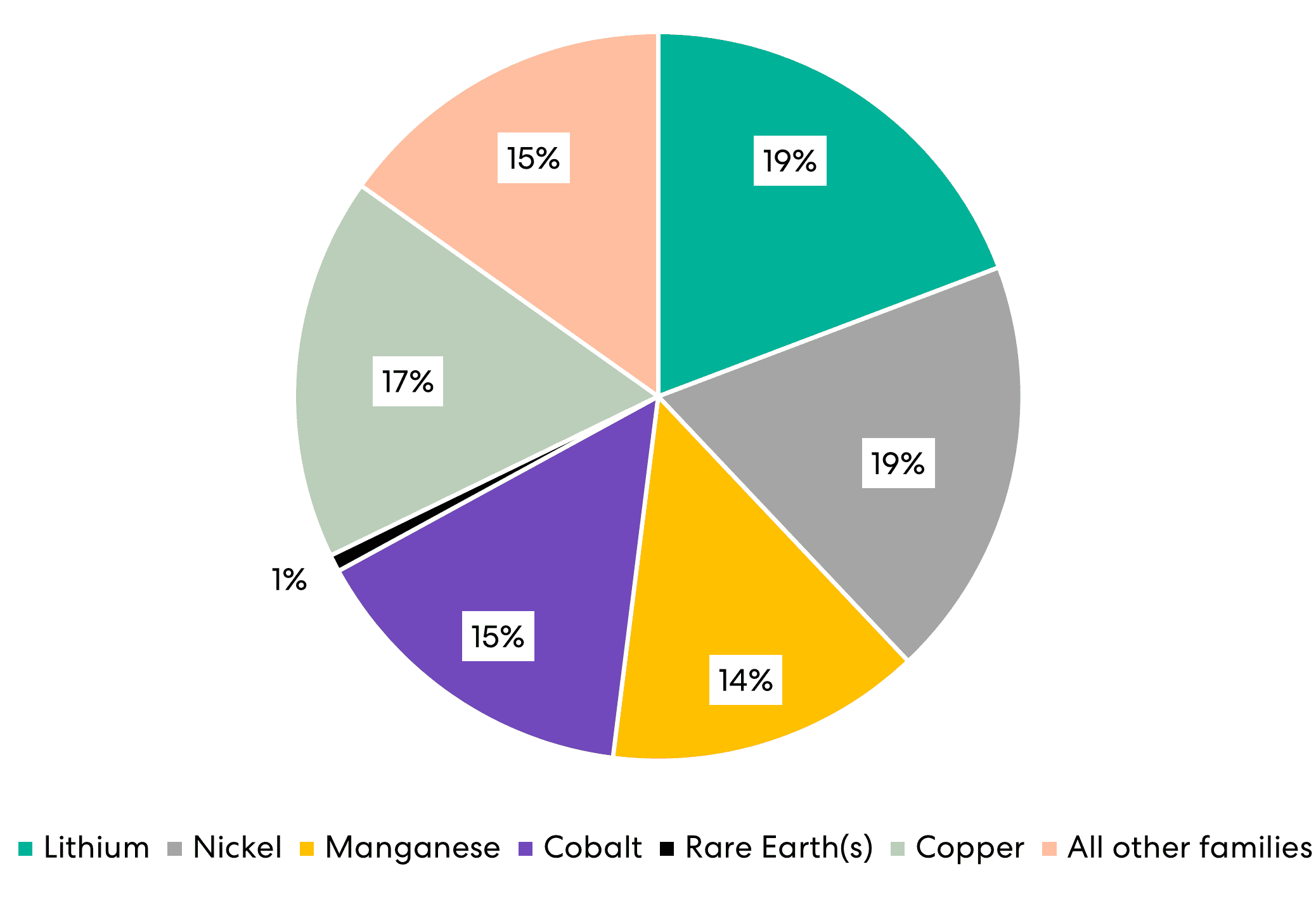

In order to determine how patent activity in the field of battery recycling is distributed between critical minerals, we performed a keyword analysis of the full text of each patent application. This analysis is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Distribution of patent applications between the critical minerals considered, using a full text analysis of the whole patent specification. Source: PatBase Analytics.

Of the critical minerals considered, patent applications in the field of battery recycling are relatively evenly distributed between lithium, nickel, copper, cobalt and manganese. Rare earth elements (as a group) are mentioned in only 1% of patent applications.

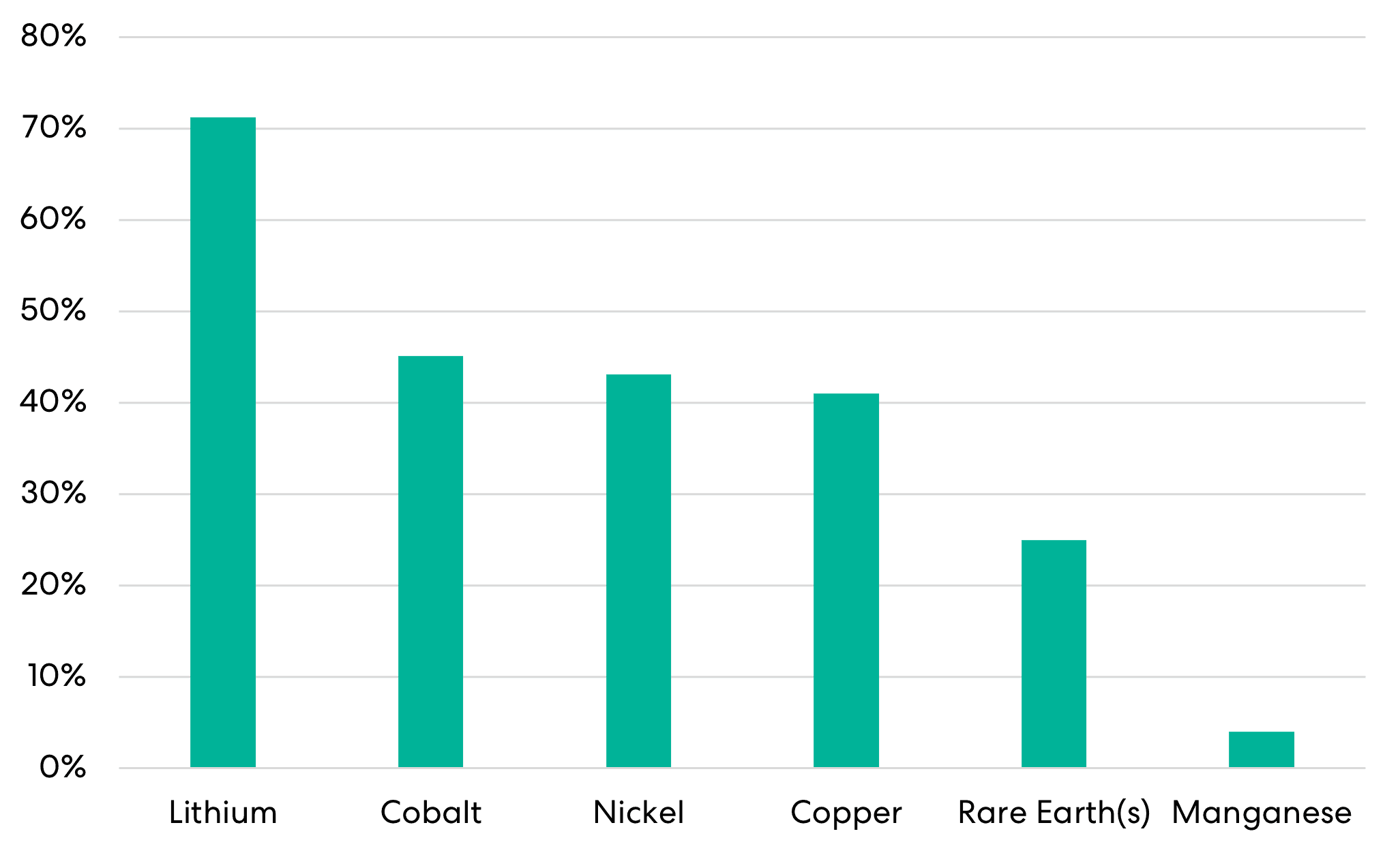

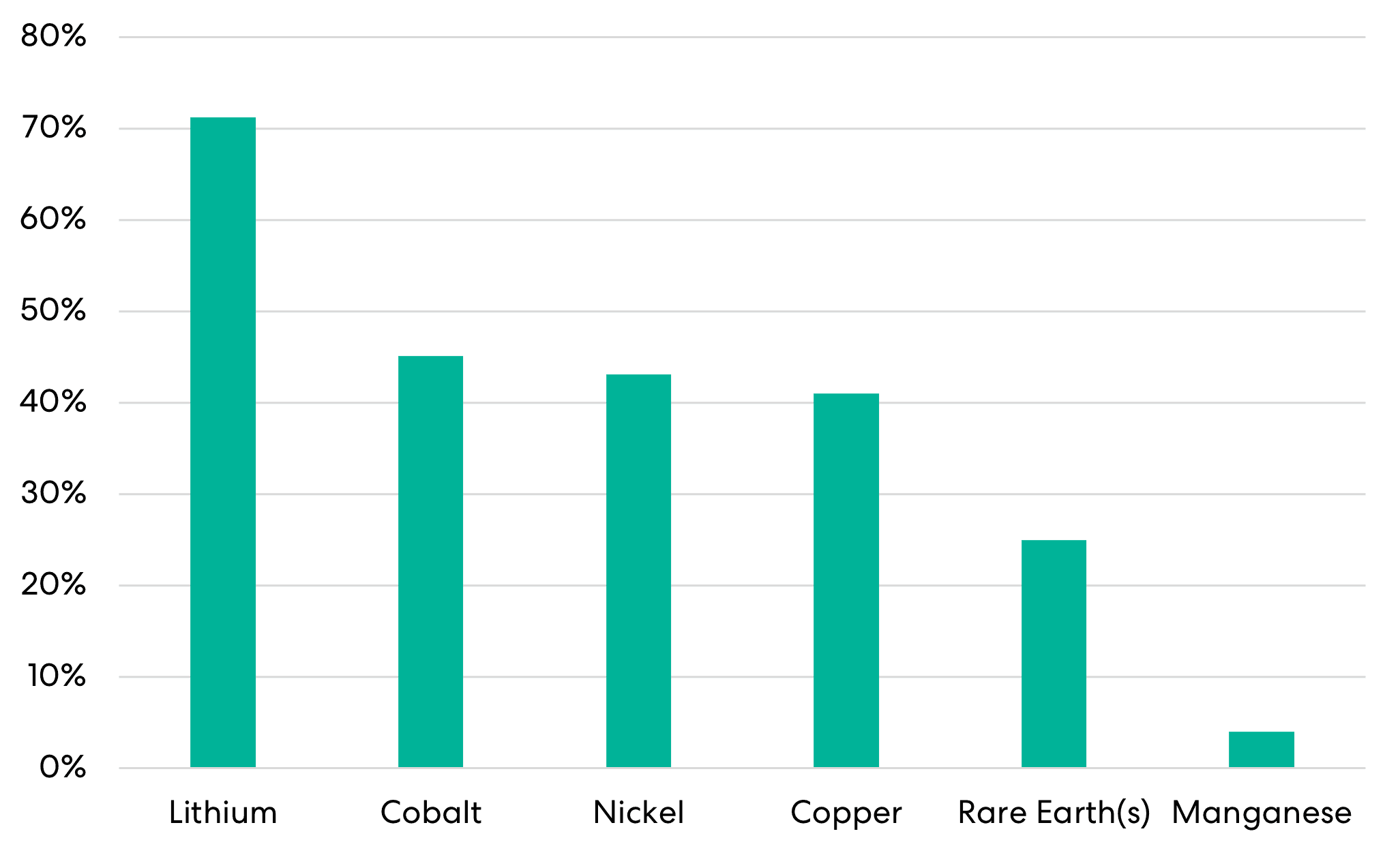

In order to focus on the documents in which the core of the invention likely involves the named critical mineral, we performed a keyword analysis of the title, abstract and claims (the “T/A/C”) of each patent application. This analysis is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6: Proportion of patent applications having the named critical mineral in the T/A/C as a proportion of patent applications have the named critical mineral in the full text. Source: PatBase Analytics.

From Figure 6, we can see that 71% of patent applications mentioning lithium are likely concerned with lithium as the subject of the invention, compared with around 40% for cobalt, nickel and copper, followed by rare earths at 25%. Manganese is significantly lower than its peers at 4%.

Accordingly, of those patent applications mentioning any of the above critical minerals, it is much more likely that an application that mentions lithium is directed towards lithium as the focus of the invention when compared with the other critical minerals.

Given that, in 2022, 60% of lithium demand, 30% of cobalt demand and 10% of nickel demand was for electric vehicle batteries[9], the prevalence of these three minerals in battery recycling-related patent activity is not surprising.