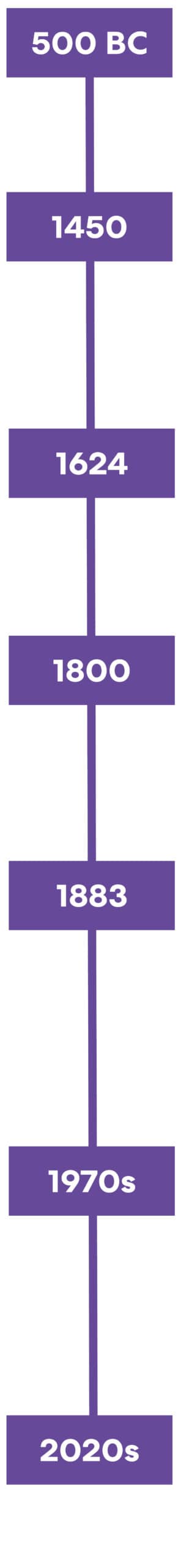

The launch of the European Unitary Patent system is now just around the corner, representing the biggest change in European patent law in 50 years. Once the system is fully up and running, a Unitary Patent (UP), obtained after the grant of a European patent application, will provide patent protection in as many as 24 EU member states with uniform effect. This contrasts with the existing procedure under the European Patent Convention (EPC), in which a European patent application must be validated on grant as a bundle of national patents in individual EPC contracting states. Here we look back at the other defining moments in European patent history.

The road to today’s patent system is a long one, widely thought to date back to Ancient Greece when discoverers of luxury products were granted short-term rights to the associated profits.

The road to today’s patent system is a long one, widely thought to date back to Ancient Greece when discoverers of luxury products were granted short-term rights to the associated profits.

A more formalised system for granting patents was developed much later in 15th Century Italy. A decree was issued in Venice in 1450 requiring new inventions to be submitted to the Republic in exchange for a limited-term monopoly. As people travelled, similar systems were soon developed in other European countries. But these early systems were often misused, with monopolies granted not just for inventions, but to everyday items. Rather than encouraging innovation, early patent systems were frequently used by those in power as a tool to garner loyalty and generate income for the Crown.

A turning point came when James I of England recognised the potential of the patent system to stimulate genuine technological advances that would in turn bring economic prosperity to the country. He revoked all existing monopolies and declared that new monopolies would only be granted for “projects of new invention”. These ideas were enforced in the 1624 Statute of Monopolies, which restricted the power of the Crown and introduced a more regulated system.

This was the system on which the industrial revolution was born. With the industrial revolution came rapid globalisation, which meant that simply owning local patent rights was no longer deemed sufficient. Inventors looked to prevent their ideas from being exploited by others around the world.

A major step towards more global IP protection came with the Paris Convention of 1883. This international agreement, now with 178 contracting parties, ensures that a country grants the same protection to nationals of other countries as it grants to its own nationals. The Paris Convention also introduced the right to priority, which gave patent applicants a year to file applications for their invention in multiple jurisdictions. However, it remained necessary to file as many patent applications as countries in which protection was required.

To relieve the burden of many separate filings, the World Intellectual Property Office introduced in the 1970s an international patent system under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). Today, the PCT allows a single patent application to be filed and later converted into national (or regional) applications in any of 155 countries worldwide.

At a similar time, the European Patent Convention was introduced to provide a legal framework for the grant of patents via a single, harmonised procedure. Once granted, the enforcement of a European patent is subject to national law, and therefore a granted European patent does not have unitary effect. To date, the only European countries to form a unified protection area (an option under the EPC) are Liechtenstein and Switzerland.

The Unitary Patent system is set to change this, providing proprietors of patents prosecuted under the EPC with the option to request unitary effect in all UP-participating EU member states. The newly-formed Unified Patent Court (UPC) will have jurisdiction over unitary patents as well as European patents designating UP-participating EU countries. Initially proposed in 2009, and having faced countless hurdles on it path to ratification, the Unitary Patent looks to finally be here.