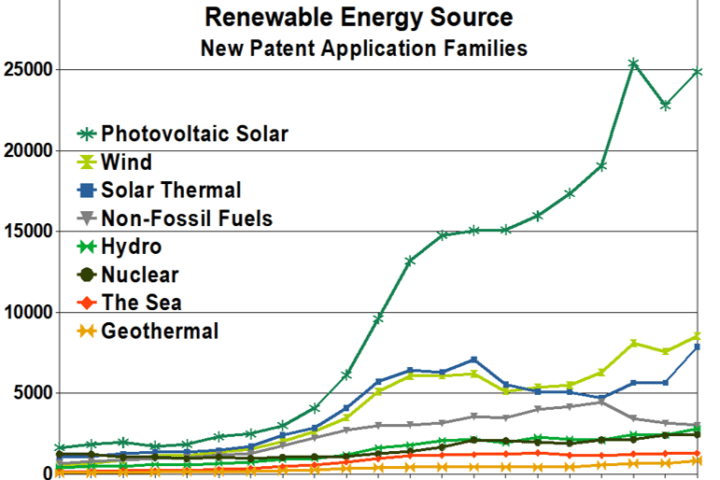

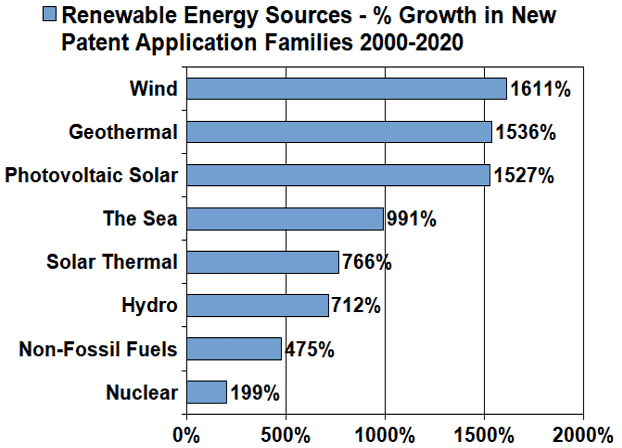

Looking at the patenting activity more closely, photovoltaic solar technology has consistently featured the largest numbers of new families of patent applications in the last couple of decades. In 2020, the number of new families that appeared for photovoltaic solar technology was roughly three times the number of new families appearing in the next most active fields – wind and solar thermal (e.g. solar towers) technologies. This perhaps reflects the fact that photovoltaic solar remains one of the most accessible green energy technologies for direct-to-consumer markets. You will no doubt have noticed the growing number of houses which have panels fitted on their roofs. Geothermal and wind energy, the other areas having the most growth in patenting activity, are also increasingly being applied on both the commercial and consumer scale. The uptake of these technologies can be expected to follow a similar trajectory as climate change becomes an increasing focus for governments and the population in general.

This recent explosion in new patent applications indicates that new, innovative energy solutions are in the pipeline and is promising in terms of reducing damaging emissions, but it could also be problematic for smaller companies or new entrants for whom minimising environmental impact is rapidly becoming an inescapable business imperative. More than ever, the public and governments expect businesses to commit to combatting climate change, and we are seeing this manifested in schemes like the Climate Pledge (to make businesses net zero carbon by 2040), and B Corp certification (open only to businesses that meet very highest standards of environmental performance). As the green energy patent landscape becomes more crowded due to the growing number of new applications, it may become more difficult for aspiring green companies to establish freedom-to-operate while also meeting their climate obligations. Consequently, we are likely to see an increase in patent litigation around the world relating to the most successful green energy technologies.

Those who hold the patent ‘keys’ to the most powerful green energy technologies will be under intense scrutiny regarding how they use their monopoly rights. They will only need to ask Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Moderna how holding the patents pertaining to life-changing technology can be both a blessing and a curse. There will be widespread hope that the companies with the most significant patent portfolios for green energy tech will use their power to lead the charge into a new, better world. Putting profit over planet in the 2020s is likely to be very bad for PR.

Happily, the proliferation of patents for green energy need not lead to the stifling of progress and can in fact enhance it. If companies view their patent rights as valuable bargaining chips which can be used to unlock the patented technology of their competitors, then they will be able to spend more of their budgets on research and building on the developments of others, and less on litigation (hurrah!).

So, for those operating in the green energy space, the age-old adage applies: the best defence is a good offence. By maintaining your own robust patent portfolio, you are likely to gain increased access to your competitors’ ground-breaking technologies. As we have seen throughout the pandemic, incredible results can be achieved when the brightest minds collaborate effectively to solve the world’s biggest challenges and we hope, like the recent quest for the COVID-19 vaccine, patents can help to lead the way.